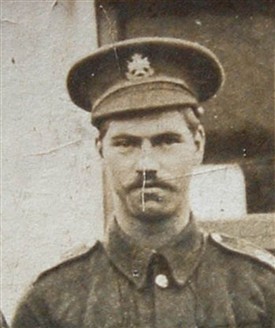

ALLEN, William Henry [of Edingley & Newark]

Pte William Henry Allen

J. Dobson

In this group of Sherwood Foresters Wiiliam H Allen may be seen standing on the back row, far right.

J. Dobson

William Henry Allen's marriage to Violet Beedham, October 1920

J. Dobson

William Henry Allen with wife, Violet (left) and daughter Grace (right) in the early 1950s outside their home on Quibell Road, Hawtonville, Newark.

J. Dobson

13357, 9th Service Bn. Sherwood Foresters

By Jenni Dobson

Born 1892, Died 1957

Born 18 Feb 1892, at 2 Melvina Place, Gt Francis Street, Duddeston, Aston, Birmingham, the fourth child and second son of what would become 12 surviving children of George Allen (b. 1865, d.1932) and Sarah nee Hobday (b.1863, d.1946).

Sometime between 1892-94, the family moved to Nottinghamshire, first to Edingley then to Newark-on-Trent , where they live in Tenter Buildings at the time of the 1901 census. This move may have been connected to the development of the town’s water mains, as George is described as an employee of the Town Corporation Water Dept. in Sarah’s obituary.

Before joining the army (no. 13357), William is recorded as a maltster in the 1911 census. His immediate elder brother Tom also volunteered, initially with the Royal Engineers before serving with the Kings Own Rifles. William Henry is listed in Appendix II (p.208) of John Stephen Morse’s book on the 9th Service Battalion, Sherwood Foresters.

William probably mustered at Markeaton Park, Derby. The battalion’s first major parade was in October 1914 when they were inspected by Lord Kitchener. On 3 Apr 1915, the Mayor of Nottingham invited the battalion to march through the city, which it did, then on to Bingham, where the men spent the rest of that day due to a heavy snowstorm. The following day they returned to camp at Belton Park, Grantham, the base of the 11th (Northern) Division of which the battalion were part, before departing on 5 Apr for a training camp at Frensham. Belton also later became the site of a major machine gun training camp.

It has been confirmed therefore that family traditions are true that William saw action at Gallipoli. His battalion sailed from Liverpool on HM Transport ‘Empress of Britain’ on 1st Jul 1915 as part of the 33rd Brigade, though it remains a mystery as to why such untried men should be sent to such a situation. The 9th (Service) Battalion landed at Suvla Bay on the evening of 6/7 Aug 1915. Some of the lighters used to ferry the troops ashore grounded on unseen shoals and consequently dropped men some way off from the beach and into water 4-5ft deep, leaving them to wade ashore carrying their rifles, packs and two days’ rations. Being a not very tall man, it may be this experience which William relived years later whilst deliriously ill and which his middle daughter remembers from helping to nurse him.

Conditions at Gallipoli were notoriously bad, both for fighting and basic living for the men. They are well documented elsewhere so suffice to say that more men died as a result of illness than were shot by the enemy. Even so, in their first assault the 9th lost almost all of its officers.

A report in the Newark Herald, 28 Oct 1916, states that William had been wounded in the side on Gallipoli then whilst recovering at the base hospital he contracted enteric (fever). When he was declared fit, he’d been drafted to Egypt (presumably to rejoin his unit at Alexandria), from where the 9th were sent to France, where they spent the rest of the war.

Family tradition said that William had been at Ypres, but in fact he was on the Somme in 1916, where, further according to the newspaper item, he was wounded in the leg and taken prisoner on 26 Sep 1916. Thanks to the above mentioned book and its account based on the war diaries, this was at the Battle of Thiepval, in the third and most forward objective, from which 2 ORs were captured, one being William. It was a trench occupied in part by the British and partly by the Germans.

My dad said that William had a narrow line on the side of his head where the hair would not grow, caused by a bullet passing between the side of his head, the top of his ear and his helmet and which knocked him out, thus allowing him to be taken prisoner. It seems possible that this may have been an additional element which contributed to his capture whilst not being significant enough to be recorded officially.

William has now been traced amongst the ICRC WW1 PoW records, on three lists which confirm this information. He was in a Kriegslazarett (military hospital) in the Hannover district (X Army Corps) and then early in 1917 was moved to a camp at Hameln, also in the Hannover district. The camp was about a mile from the town itself and was a ‘parent’ for many work camps. Having known for a long time that William had been sent to work in salt mines, I had previously assumed that these were in Siberia & that he’d therefore been captured whilst at Archangel. However, Steve Morse was stationed in the Hannover area whilst a soldier himself and confirms that there were salt mines nearby. Richard van Emden’s book ‘Meeting the Enemy’ suggests that any prisoners who earned themselves a reputation as troublesome would likely have been amongst the first to be chosen when a camp commandant was asked to supply workers for the most unpleasant tasks. I could imagine William might well have come into that category!

He also had a deformed little finger on one hand, which I once asked about as a small child. I was told not to talk about it, but later my father explained that whilst he was a prisoner, things were so bad that William laid his little finger on a railway line & let a truck run over it, so that he would be taken to the camp hospital where conditions would be slightly better. As a little child, of course the only trains I could picture were passenger trains but doubtless, in this case they would have been the rail trucks which were used to haul the mineral out of the depths of the mine.

My dad once said that when William was eventually freed, he walked the rest of the way back home (we assume not walking across the Channel!). He reckoned it had taken William about 6 weeks and he also believed that William had tried to hand himself into the authorities (which ones I don’t know!) but they were not interested.

This fits in part with personal accounts in the van Emden book mentioned above. There appears to have been no organisation to repatriation. Some guards simply opened the gates & left the prisoners to fend for themselves. At some camps they found a store of ‘Red Cross’ parcels (these were not supplied by the Red Cross, who simply shipped parcels sent by prisoners’ aid organisations to the camps) and van Emden describes how on one occasion the newly freed men gave away some of their parcels’ contents to starving local people. At others, as described in a Newark newspaper, the guards handed out such parcels to the departing prisoners as they were loaded onto cattle trucks being sent to the Dutch border.

Finally there is also a well-established family story that, though the 9th Battalion did not go there, William went to Archangel, a key port in the Allied campaign in North Russia whose purpose was too complicated to explain here. Having established the truth of the other aspects of William’s story, I am reluctant to dismiss this as a fiction, the more so since discovering a friend who grew up with the same story about her grandfather, Harold Garner, who had joined the Sherwood Foresters also. Steve Morse, author of the 9th battalion’s book, has suggested that possibly when William returned to England, he could have volunteered for the Expeditionary Force being sent to North Russia because he felt that he had sat out the war in a camp for the best part of two years. This remains to be confirmed or disproved but is a research challenge due to the very limited amount of information available on what was eventually a complete failure.

Whatever is the case, William was back in Newark-on-Trent by 26 Oct 1920 when he married Violet Beedham. They had seven children, (though one died at birth) and their baptismal records allow the tracing of his occupations at these times.

The eldest child Charles Henry was born 1 Feb 1923, and baptised at St. Leonard’s church, Newark on 23 Feb 1923, where William’s job is given as malster. Charles died 17 Jul 2007 and I am his only daughter, and first grandchild to William and Violet.

Their next child was born 1925 and baptised also at St Leonard’s, as were all the following baptisms. William was then a general labourer. Next came a son in 1931, with the family address given as 8 Elgin Place and William’s job as labourer. The same details are noted at the 1933 baptism of a second daughter. By the time the third daughter is baptised in 1936, William is working as a pipe jointer but when their youngest child is born in 1940, William is a brewer’s labourer.

William’s surviving daughter thinks that during WW2, he worked for the local council in some capacity as she remembers him being injured at work, possibly lifting something heavy off a vehicle.

William’s work as a malster reflects one of Newark’s main businesses, with companies engaged in this activity associated with the beer brewing industry which was also prominent in the town. His health was permanently damaged by his WW1 experiences, particularly exposure to gas, as he always had a bad chest. He died 18 Oct 1957, his daughter thinks from a bout of Asian ‘flu, and is buried in the London Road cemetery, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire.