BROWN, Vincent Archer Alphonso [of Southwell]

![Photo: Illustrative image for the 'BROWN, Vincent Archer Alphonso [of Southwell]' page](/images/uploaded/scaled/Brown_Vincent_of_Swell___Herald_7_Oct_1916_s1_s.jpg)

From 'The Newark Herald' 7th October 1916

Vincent's gravestone - shared with his brother Francis - in the churchyard at Southwell Minster

Photographed september 2014

The Chemin des Dames in the Great War

French infantry attacking

The Chemin des Dames today

Guillemont Road Cemetery

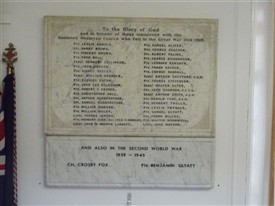

Southwell Methodist Church war memorial

Including Vincent Brown

By Mike Kirton

Born: 1889. Killed in action 13th September, 1914

Professional Soldier: 2nd Battalion, Sherwood Foresters.

Vincent Brown, born in Nottingham, was educated in Southwell and was the second son of Charles and Mary Brown. In 1907, aged 18, he enlisted with the 2nd Battalion, Sherwood Foresters and had been based in Wales, Plymouth and Sheffield prior to going to France in September 1914. His battalion took part in the Battle of Aisne, being in action at Chemin de Dames, where they suffered heavy casualties. Shortly afterwards they moved north and took part in fighting around Hooge in 1915. In December 1914 he wrote a long letter to his parents describing his harrowing experiences. Extracts from the letter were published in the Newark Advertiser on 23rd December (see the Southwell War Diary).

‘A SOUTHWELL SOLDIER HIS ADVENTURES WITH THE SHERWOODS The following extracts are from a letter to his parents in Southwell, written by Private V. A. A. Brown, a signaller in the Sherwood Foresters, and published in the Nottingham Guardian:– “On the 19th September we took over some trenches for a few hours. Here was where we got our first man wounded (by shrapnel). Early on the 20th September (Sunday) we relieved the Queen’s Regiment, two companies in the firing line, and two in support. Here is where the fun started.

About two in the afternoon we were all sitting about the dugouts. We saw a lot of our men coming over the sky-line on our right. We did not know who they were at first, but did so soon afterwards. All glasses were focused on them. We didn’t know until we saw one up a telegraph pole cutting a wire. They were coming over the sky-line in hundreds. Down comes the general. Our commanding officer says, “They have taken our trenches”, “No,” says the general. “They have, sir,” says our commanding officer. The general had another look. “Yes,” he says.

THE WORST PART OF THE LINE

Then the orders came – A and C Companies in the firing line, B and C in support. We had got the worst part of the line to attack, too, but off they went. As soon as they came over the crest of a little rise our fellows met a murderous fire. The Germans had got several machine guns hidden in a haystack and they caught us in the flank. We had to go over a little rise down a hollow and the enemy was on the other ridge, and they were still running over the other ridge. They were in and out of our trenches in a little over half an hour.

The West Yorkshires were coming over in solid masses, but our fellows went up that hill like a lot of madmen. The Germans never stayed to face the bayonets but we lost a lot that day, about 250 killed and wounded. One of our sections got caught by a machine gun just as they came out of a wood. They all lay dead nearly in a straight line with the officers in the centre.

We saved the situation, but at what cost? As soon as the West Yorks saw us coming they turned and joined up, what was left of them. Of course, they were retiring, also the Durhams on our left. I can honestly say if it had not been for the Sherwoods the situation would have been lost there, and I expect the battle of the Aisne would have been lost to, as for several days that part of the line was the key to the situation.

One of our officers, Mr Barnard, was leading his men, swinging his walking stick in one hand and his revolver in the other. He got wounded once but still went on, and got killed before he got to the trench. I think the bravest man was Captain Popham. He was wounded five or six times, nearly all in the head. Although his face was streaming with blood he kept on shouting, “Come on lads, get at the devils.” One man wanted to bind him up but he said, “Get on, lad, with the others.” He is Irish, so you can understand.

On the 19th October, at night, we took over some trenches at Ennetieres and that night passed off all right. About seven next morning they started shelling, and one burst just outside the house we were in and shifted all breakfast pots off the table. We shifted out there quick and went on several more miles before the day was over.

Well, about four in the afternoon – the shelling was on all day – the Buffs [Note: Royal East Kent Regiment] on our right retired, and we didn’t know that we had lost a lot during the day, though we had a lot more to go through before the day was over. The C.O. sent down to the general to say they were closing on our trenches. The general says you must not retire on any account, so the general sent to the trenches that message. But we got an order to retire, what was left, of course, and you ought to have seen the thin khaki line nipping down the road. We went into action 973 strong that day, and at roll call next day we mustered 243 all told. Just fancy, we had lost 730 in one engagement but I believe 500 or more were prisoners. There were some bad cases among the wounded, too.

Well, we nipped down the road, and it was swept by shell fire and two machine guns all the way until we got over a rise and got against some sand pits.

I will tell you what the Germans had done. There was a big fort, called Fort Aiglais; it was one of the outlying forts of Lille, and the Germans knew if they could get a house down there they could sweep the road we had to retire down. So we shelled this house until they knocked the corner off and then their maxims swept straight down this road. A lot of our chaps had been captured by this time. Some of them got away from the Germans though. We retired down the road under fire, and when we got over this little rise we thought we should be safe, but the Germans had got round on our right and the sandpits came under fire from the right. Bullets were whistling around us. The general says: “Collect all the men you can and line that ridge on the left.” There was a windmill there. And it was about 8 by this time and fairly dark. We lined the ridge by the windmill and all the C.O. could muster first was 83 of us. I got sent out on lookout to a burning house about 20 yards to the right of this windmill. The Germans charged our chaps so they had to retire, and we got the order and got left there. We got to know later that a whole Brigade of Germans charged our 83 men. We heard the Germans yelling “Hoch! Hoch!” [Note: ‘High’]. Then we thought it about time to move, so we moved. We could not go through the village, us three, as the Germans were in possession of it, so we went across country and found the battalion next morning three or four miles away. We got there just as they were having breakfast, so I was all right. It was about the worst night I have had, and the tightest corner I have been in. I thought my time had come that night, especially when the Germans got up to the windmill. We crawled away very quietly, I can tell you.’

Little more was heard of Vincent Brown until 1916, when the 2nd Battalion were taking part in the continuing Battle of the Somme. On 13th September ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies were moved to just south of the village of Ginchy, with ‘A’ and ‘D’ Companies in support in the reserve trenches. Around 4.00 a.m., after the attack had gone in, a patrol was sent out to find them. It appeared that ‘C’ Company had been held up and ‘D’ Company had managed to advance about 700 yards under heavy shelling and fire. ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies were able to hang on to their gains. However, the battalion suffered heavy losses, including Vincent Brown on 16th September. He is buried at Guillemont Road Cemetery, Guillemont. Vincent Brown left a widow, Mary E. (Haywood), whom he had married in late 1913.

Vincent Brown's father, Charles Brown and elder brother John Harry Brown also served in the war.