Hidden Voices

Civil War re-enactment at Newark Castle

Musket, drum and pike

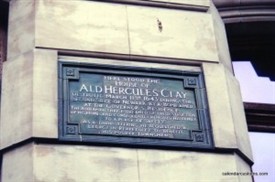

Hercules Clay house plaque

Newark Siege tokens

OBS = Obsidium [Latin: Siege of]

Newark's civilian experiences during the English Civil War years of 1642 to 1666

By ROGER PEACOCK

Hidden voices’: this was the sub-title under which Rev. Dr. Stuart Jennings, Free Church Chaplain to the University of Warwick delivered his refreshingly different portrait of the English Civil War as it was experienced in Newark. It was different in so much as it did not focus purely on political and military personalities. Both of these areas are well-documented in the town's local studies departments. Rather Dr. Jennings presented the evidence by which the lives of ordinary townspeople – the likes of the butcher, the innkeeper or the blacksmith – were affected by the besieging of the armies of Parliament. The farmhand must not be forgotten. Newark was a very different township to that of today. Its environment, not just in the surrounding villages but also within its town boundaries, had very much a rural flavour; farmsteads stood where homes or shops now throng, and farm animals had an accepted place in the streets.

These aforementioned were the characters who were trapped in their home town without supplies of fresh food, medical provision or any basic need, alongside the unaccustomed dangers of cannon fire and horseback skirmishes with pike and musket. Yet these were also the people who rallied together in force to oppose the intruders, even when their own weapons were little more than pitchforks. How is this known? This was the question to which Dr. Jennings detailed answers, evidence that he had accumulated over years of personal research.

Firstly, the speaker said, there was the evidence of architecture and archæology. The Queen's Sconce is Newark's example of surviving siege works, whilst sufficient remains of Newark Castle to speak for itself of the experiences of a township supporting King Charles I against the opposition of the Parliamentarian military. There are also town-centre buildings, notably the Governor's House in the Market Place and the Queen Henrietta Coffee-house in Kirk Gate, which stand as witnesses to this period in history. The nearby St Mary's Church spire retains its perforation from a Parliamentary cannon-ball, purported to have been fired from Beacon Hill. The Old White Hart was a travellers' inn at the north-eastern corner of the Market Place, in the early mediæval building now occupied by the Nottingham Building Society and the range of shops behind This provided both Staunton's offices and stabling for his horses.

Much of the Castle was dismantled after the surrender of the Royalists, a visual fact that attests to its defensive rôle in the sieges to which Newark was subjected, a purpose which the victorious army ensured could never be repeated. But, suggested Dr. Jennings, was priority given to destroying the right section? In his view demolition of the gatehouse, the curtain-wall, and the tower wrongly purported to have accommodated King John, along with the dungeons and crypt beneath the Castle, would have been a more effective deterrent. Yet much of the visual heritage survived both the ravages of bombardment and that of plague (see later note on the latter). Whilst no explanation other than Parliamentary haste can be offered for the choice of demolition target – the intention was probably to dismantle the entire structure – historians have certainly benefited from the visual evidence that was retained.

More important is the documentary evidence that has been unearthed within the archives ofNewark District Council, as it was known at the time. They came across several boxes, now in the possession of Nottingham Archives, containing paperwork dating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. These were counterfoils, retained notes of ordinary civilian activities during this period. It is the siege period of the Civil War that holds the most interest in the light of the town's significance to the Royalist struggle. Alongside these are the records of the Borough Council minutes, churchwardens' accounts, and other civil matters of the time, all of which pay homage to the everyday personalities to whom previous reference has been made, and who are in some cases named. In essence, the civil records seem to leave few gaps, although no record was included of military personnel who were garrisoned in the town to aid its defence. The reason for this, of course, is that army records were a separate matter, and were not the property of the Borough. It was noted that soldier billeting would not have been in the Castle itself, as archæological findings reveal no facilities for this. Rather would they have been accommodated in residences amongst the townsfolk themselves. That fact is verified by noting the increasing population of the town during the course of hostilities; from two thousand to occasional figures of six thousand, a statistic which could be accounted for in no other way. This in itself suggests that the ordinary people could not have avoided involvement in the events of the time. With the King's army living alongside them, they must have felt affiliation to the Royalist movement on a personal basis, and may have talked to or with the soldiers when the opportunity arose. That these same Newark civilians were prepared to rally for the cause of the town is certain, as it is known that they came in force, probably armed with little more than pitchforks, to oppose an attacking body of Parliamentarian support from Lincoln. Such did this show of defence confuse the attackers that they could not see what to do next. Obviously the volume of Newark support was sufficient to offer a deterrent and maybe even a threat. Anyway, the Lincoln contingent decided to apply discretion as the better part of valour. So off they went. In fact, items of the Newark brigade's blue seige uniform, along with written receipts, were amongst the contents of the aforementioned box. Thus it can be held up as evidence of the civilian involvement in the political forum.

Most of the key political and military personages made a visit to Newark during the Civil War. King Charles and Queen Henrietta were just two of the Royalists who had been seen in the town, and who were accommodated overnight. Another royal visitor was Price Rupert. Some prominent Parliamentarians, including Oliver Cromwell, were also in the vicinity. Let there be no doubt that the town of Newark featured highly on the Civil War agenda. No city or townstead would have overshadowed its significance. Indeed, there are Parliamentary records of this as well as local ones. It is for this reason that promotion of Civil War heritage is to be placed alongside local popular culture in a new museum venture.

How effective, then, were Newark's defensive structures? The mediæval walls would have been no match for seventeenth-century canons, and they were becoming less relevant owing to changes in the town's boundaries. The Trent and river crossing could only delay the entry of an attacking army. Indeed, Dr. Jennings related, there were householders who were ordered to dismantle their homes on site, and re-erect them in less vulnerable environs deeper within the town. As timbered or half-timbered houses were the norm, this was easy to accomplish. It was the insufficiency of protective facilities that led to the strategy of earthworks as demarcations. Interestingly, these are more adequate than stonemasonry, and in a rural community, there could be no shortage of resources. They were, in effect, extensive mud banks, reinforced with turf and dried into solid barriers, which could easily absorb the impact of canon and shot. Unfortunately, their erection was to the detriment of neighbouring grazing-land, an essential element in a rural community.

These extensive earth works meant that the English Parliamentarian army besieging to the south and east of the town had to construct and man their own siege line to restrict any royalist breakout. Their allies in besieging the royalist garrison, the Scottish army, consisted mainly of cavary and were based to the west and north west of the town behind the two branches of the river Trent. Unlike their English counterparts who were recruited from and supplied by the Midlandshires, the Scots were dependent on supplies and pay from London. Initially, these were slow to arrive. On the whole, the Scots army was poorly-paid and lacking in discipline in comparison to their English allies.

The biggest hazard of the sieges of Newark was the prevalence of typhus deaths, especially amongst closely-packed defence forces who were often unwashed for some time, and dressed in unchanged clothes. But the civilian death-rate was also high. Thatched roofs were virtually non-inflammable, so Parliamentary mortar attacks could not cause destruction by fire. All three sieges occurred in winter. But nor could they eliminate plague, The second of the three sieges was the most devastating in this respect. The black rat, the carrier of deadly bacteria, could survive by hibernation, allowing recurrent outbreaks. The burials graph tells a sorry tale of the time, although that of Nottingham – a Parliamentary stronghold – is higher, an unexplained fact. The discovery of the local records has revealed all this, with the exception of military statistics, and has been the most useful resource to Civil War historians.

Dr. Jennings' revelations were most interesting and thought-provoking.

© Roger Peacock for NALHS: 3 rd December 2013

Edited by Rev. Dr. Stuart Jennings