May Day In Nottinghamshire

'Merrie England'

Paul Nix Collection

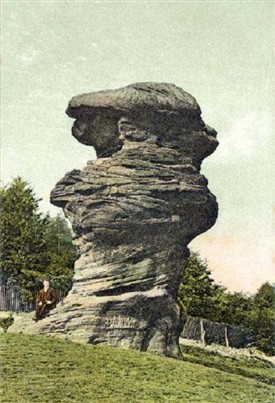

The Hemlock Stone

Nottingham Hidden History Team

The Druid Stone

The Megalithic Portal

Wellow May Day Celebrations in 2010

Foresters Morris Men

Robin Hood with May Blossom

Foresters Morris Men

by Frank E Earp

By Joseph Earp

This year [2013], as I have for the last ten or more years, I will be celebrating May Day in one of the time honoured ways. I will be up before dawn on the 1st May and as the sun rises over the City, I will be dancing the Morris by the statue of Robin Hood on Castle Gate. I won’t be alone of course, but with my fellow dancers, the Foresters Morris Men. If we are lucky there will also be a small, but appreciative audience.

Why celebrate May Day? Here, folklorists, including myself, would normally ‘trot-out’ a list of complicated reason. However, this list seldom includes the most important reason of all, ‘for the sheer pleasure of celebrating’.

From the earliest of times, humans have measured the passage of time by observing the heavens. The rising and setting of the sun, moon and bright stars has been used to calculate not only night and day but the seasons of the year and to predict future dates.

The sun’s apparent progress across the sky, the solar or natural year, is punctuated by four major events; the Summer Solstice, (21st June) the Winter Solstice (21st December) and the Vernal and Autumnal Equinox, (21st March, 21st September). By observing and marking the sunrise or sunset on each of these days it is possible to maintain a rudimentary calendar of the four seasons. Observations of the natural cycle of the moon were used to divide the natural year into days, weeks and months.

With the advent of agriculture, it became necessary to create a more accurate calendar, marking the times for ploughing, harvesting, lambing and other important agrarian and pastoral events. For this purpose four days were inserted between the solstice and equinox days, thus dividing the year into eight.

By the time of the pre-Christian Iron Age Celts, over 2,000 years ago, these ‘quarter days’ became part of an organised calendar and were given names. In this ancient calendar, the year began with Samain, 1st November, = the gates of winter and the time of the ancestral dead. Imbolc, 1st February, = start of spring and time for lambing, Beltane, 1st May, = summer’s beginning and the middle of the year, and Lugnasadh, 1st August, = the time of the harvest and first fruits. These four days became known as the four ‘fire festival’, from the habit of lighting a bonfire on the preceding evening. In a preliterate society, partly in order to pass-on knowledge of the calendar to the next generation, these named days became the time of great celebration

There is evidence which shows that two of Nottinghamshire’s famous geological features, -the Hemlock Stone and the Druid Stone, and the Cat Stone, – a stone placed into the landscape, were used in the creation and celebration of this calendar. The antiquarian Spencer T. Hall records that in his youth, older people spoke of memories of the lighting of a bonfire on May Eve, on the top of the Hemlock Stone at Bramcote. The ancient Ewe Lamb Lane, part of a prehistoric highway, which once led to the foot of the stone, may be a further lingering reminder of May Day celebrations.

At Strelley, just over 1¼ miles north of Bramcote, is a mini version of the Hemlock Stone, part of the Catstone complex. This author has evidence to demonstrate that it was used 4,000 years ago in the Bronze Age, as part of the observations of the sunrise on 1st May between 1800 and 1700 B.C.

The County’s second largest natural geological feature, the Druid Stone, a.k.a. Alter Stone, has at some point in its history had and artificial cave cut into its western side, with a ‘window’ opening providing a view to the east. Since at least Victorian times it has always been believed that this feature was cut in ancient times to observe the sunrise on the morning of the Summer Solstice. However, a survey carried out by this author and two colleges in the 1970’s, proved that the window was cut to observe sunrise on 1st May again between 1800 and 1700 B.C.

The Saxons called the month of May ‘Trimilci’ – thrice milked, this time domestic cows are said to give three times more milk than normal. It is from this association with milk that the ‘Milk Maid’s’ dance on May Day is believed to have originated. In many parts of the County, Milk Maids would arise before dawn and wash themselves in the dew from the hawthorn tree. After this ritual ablution, they would proceed to dance in the streets of their village or town, balancing on their heads as many containers of milk as they could manage.

Hawthorn is a plant sacred to many cultures and has particular associations with this time of year. However it is the blossom of its cousin the blackthorn that is truly known as ‘May Blossom’ or simply May. A local say referring to weather lore, gives advice as to when it is safe to start to remove items of winter clothing; ‘Narre pass a clout to May is out!’ – ‘don’t take anything off until the blackthorn has blossomed!’ Although it was lucky to hang May Blossom above the door, affording protection from witchcraft, it was considered unlucky to bring it into the house.

In Tudor times, the name of Nottingham’s own Robin Hood was synonymous with May Day. Celebrations were often referred to as Robin Hood Games and the day itself referred to as ‘Robin Hood’s Day’. Robin and his consort Maid Marion were the central characters in a play and the two were counted as the ‘King and Queen of the May’. It is of no surprise then, that the name Robin Hood appears in records and accounts of May Day in Nottinghamshire.

Tudor celebrations were noisy and rumbustious affair, beginning on May-eve with the lighting of a bonfire. Guns were fired and small quantities of gunpowder exploded with the same effect as modern fireworks. Led by the Mayor and councillors, the people of Nottingham paraded to St. Ann’s Well on May morning, to celebrate. Surviving records dated from 1541 to 1579 show expenses charged to the town’s funds;

1541:- 16d charged for wine on May Day when we rode May, also to Master Stapleton in other ways. With 8d given to Master Thomas Skevynton when he and other young men brought in May of May Day, with Master Mayor.

1549:- Nottingham chamberlains paid 4s to the waits for playing to St. Ann’s Well the Monday in Easter week before the Mayor and for May Day, – ‘6s 8d reward gevyn unto the Daunsers that bough in May. With 10s, at the same time to gunners and for powder.’

1572:- 24s paid by the town to gunners, dancers and others that took pains and for gunpowder on Sunday after May Day. And 1s 4d paid for gunpowder and match and 2s for setting the Watch with 18d for two men going with their drums.

1573:- 21s given in reward on May Day to gunners, dancers and others and for 5lbs of gunpowder.

1575:- £3 2s 6d was spent on bringing in May Day at Nottingham.

1576:- ‘10s paid unto serteyne dauncers and others that dyd binge in Maye before Maister Mayor on Sunday after May Day.

1579:- 6d paid to the Stapleford who came with a May Game.

The end of the 16th century saw the rise of a more puritanical Christian faith and the attitude of the Church towards May Day celebrations became less tolerant. Records for Nottingham show that in 1605, a local man, Peter Roos, appeared before Church authorities having admitted to participating in the ‘maye game’ during service time.

In 1608, May Day once again fell on a Sunday. As part of the celebration, a football match was held, again during service time, on the Meadows, now the Meadows district. Attendance in church was compulsory for all and although the players appear to have escaped, eleven men returning home from the match were prosecuted.

It was not just May Games and football matches that fell afoul of Church law. Church court records show that on 16th October, 1585, Robert Dewych of Boughton in Nottinghamshire, was cited in that; ‘….he did set up a Maypole in ye church yard’

Sometime in the early years of the reign of Charles I, an incident occur in Nottingham which led to one of the lengthiest cases in British legal history. One Sunday morning, the vicar of Gedling, Rev. Truman, was riding through the village to visit a sick friend. On passing the village-green he saw a group of men and women gathered around the Maypole preparing it for use. Truman, angered by the sight, rebuked the wayward souls for the actions but was informed that they were breaking no law. He replied, “You may be obeying the King’s Law, but you are not obeying God’s.”

Truman decided to take out a private prosecution against the Maypole decorators. Having cost £1,500, and lasting nearly a year, the case was unsuccessful and Truman died a bitter and broken man.

Of all things associated with May Day the most iconic is the Maypole. The image of the Maypole, with children dancing around holding ribbons, is comparatively recent. The small pole with ribbons is known as a Continental Maypole and was introduced from Europe, partly under the influence of the Victorian, John Ruskin. The true English Maypole are tall, many over 60ft, and formed the centre of a spiral or ring dance with the dances, of all age groups, holding hands. Some poles were erected annually for the occasion, but most were permanent features.

It is true to say that before the English Civil War, almost every town and village had a Maypole. With the Civil War and the Commonwealth, May Day celebrations were band and the Maypole disappeared for almost a generation. With the Restoration of the Monarchy, – Charles II, – May Day celebration once again became popular and some poles were reinstated to their place of honour on the village green.

There are records of 12 village Maypoles in Nottinghamshire. In alphabetical order they are; Bradmore, Boughton, Clifton, Farnsfield, Gedling, Gotham, Hucknall Torkhard, Linby, North Wheatly, Nottingham, Stapleford, and Wellow. With the exception of Wellow, and Linby, all of these poles have now disappeared.

In recent years a new permanent pole has been erected in Linby. However, modern health and safety rules have not allowed it to occupy the traditional site next to the ‘Top Cross’. Planning regulations dictate that it is painted white and is only around a quarter of the height of the pole removed in the 1920’s.

The earliest written reference to a pole at Wellow is 1835, but tradition states that it is a survivor of the ancient Maypoles. The current pole, replacing its predecessor, was erected on 7th February 1976. Made of steel and painted in the traditional red, white and blue spiral, this pole stands at 55ft tall, 60ft including the weather vane. The good folk of Wellow are rightly proud of the Maypole and public May Day celebration take place on the Village Green every year on the Bank Holiday nearest to May Day.

The Foresters Morris Men dance every year on the 1st May. The side dance nearby the statue of Robin Hood. Dawn is usually at about 5.20 a.m. at that time of year. The Foresters are usually joined by the Greenwood Step Clog dancers. Other Morris dancers are welcome and if we know in advance you may well be invited to breakfast afterwards. So if you happen to be up at dawn in Nottingham on the 1st of May, why not come down to the Robin Hood statue and watch an old English custom being performed.