Mr. Brannan's Diaries

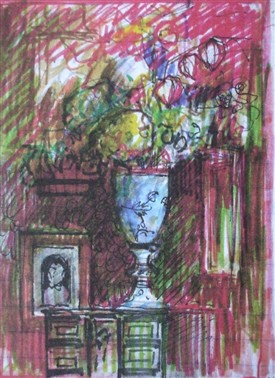

"Interior"

Private Collection, courtesy of the Artist's Estate

Study for "Interior", Peter Brannan, Diary 4, 19th September, 1987.

Courtesy of Artist's Estate

Two studies for "Still Life", Peter Brannan, Diary 7, 1st June 1990.

Courtesy of Artist's Estate

Study for "Snow Scene", Peter Brannan, Diary 4, 22nd November 1987.

Courtesy of Artist's Estate

Study for "Still Life", Peter Brannan, Diary 7, 8th June 1990.

Courtesy of Artist's Estate

Study for "Interior", Peter Brannan, Diary 3, 8th February, 1987

Courtesy of the artist's estate

The Diaries of artist, Peter Brannan - an Introduction

By Dr Malcolm Moyes

From the late 1980’s, until a few months before his death in 1994, the artist Peter Brannan kept meticulous diaries which recorded his day to day life in Welbourn, Lincolnshire, where he had lived for over twenty-years. As well as extensive and detailed text, the diaries also contain many coloured drawings, usually done in felt-tipped pen, which record ideas relating to work in progress.

All twelve diaries provide invaluable insights into both Peter Brannan the man and Peter Brannan the artist

Each of the extant diaries is both numbered and dated as follows:

Diary 1: 10th November 1984 – 21st June 1986

Diary 2: 22nd June 1986 - 31st January 1987

Diary 3: 1st February 1987 – 16th September 1987

Diary 4: 17th September 1987 – 30th May 1988

Diary 5: 31st May 1988 – 20th January 1989

Diary 6: 21st January 1989 – 12th October 1989

Diary 7: 13th October 1989 – 19th November 1990

Diary 8: 20th November 1990 – 24th May 1991

Diary 9: 25th May 1991 - 6th November 1992

Diary 10: 7th November 1992 – 3rd August 1992

Diary 11: 4th August 1992 – 7th February 1994

Diary 12: 8th February -28th November 1994

A reader expecting a plethora of explicit information which would provide definitive evidence for the putting together of a complete catalogue of Brannan’s later work will be both disappointed and frustrated. When working on a new picture, the artist usually refers to it generically: for example as “a little beach scene” or “yet another Interior” or merely “the Still Life”. The difficulties are sometimes compounded by the fact that he frequently worked on three or more different paintings at the same time, unhelpfully and indistinctly referring to “the new picture”. Drawings on the page are sometimes valuable in their approximation to a known painting, but are probably more useful as a supplement to an understanding of the false starts, changes of mind and technical frustrations recorded by Brannan in the text, as a new painting slowly, sometimes painfully, evolved.

There is a similar lack of precise information when he records a painting being purchased directly from his Welbourn studio, as was sometimes the case: there is rarely an individual identification of a work by title or by detail, although the particulars of the transaction are often helpful in terms of identifying patterns of ownership over time. An important exception to this silence is when Brannan mentions a commission piece being discussed with a client, accepted and then, in due course, collected from his home.

An additional frustration for the reader intent on accumulating information about Peter Brannan the artist in general is that characteristic diary entries for each day do not focus for very long on painting, but rather upon mundane day to day living and a seeming continuous whirl of social engagements. In a sense, this is not surprising, as his painting was organised, on the whole, as a small part of a fixed daily routine of work and play: typically around one and half hours in the late morning or early afternoon, and occasionally an additional session later on in the day. Whilst it is clear that painting was an absolute necessity in his daily life, it is equally clear that there were times when working in his upstairs studio became an unwelcome burden, an irritating commitment to what he disparagingly describes as “duty painting”.

It is true that the odd throwaway remark and the all too rare detailed description of key images in a new painting provide suggestive clues about a Brannan work, as does the occasional annotated small drawing embedded in the text. However, all too often, the reader is left struggling to piece together tantalising, but ill-fitting fragments, into a precise and coherent account of his work during these years.

It is perhaps because of this general lack of absolute clarity and expansiveness, therefore, that the reader becomes almost grateful when discovering unambiguous statements by Brannan about his working life as an artist or detailed commentaries on what he was trying to achieve in a specific painting. That gratitude is further enhanced when the work in question can be identified as now being in a private or public collection, or as having been sold at auction. The diaries at these critical junctures provide material that is sometimes surprising, occasionally quite astonishing, and which is central to a broader understanding of this enigmatic artist’s work as a whole.

Throughout the diaries there are references to what Peter Brannan called “the reject pile”. It is evident from the context of some of these references that the paintings in the reject pile were not just works which the artist had abandoned as unsatisfactory and in need of improvement, but also paintings which had once been exhibited and had failed to sell. The initial rejection of some paintings in the discarded pile was not by Peter Brannan, it seems, but by the art buying public.

On at least two occasions during this period, unsold paintings from the 1950’s were bought from the Welbourn studio, where they had lain untouched in the ‘reject pile’ for over thirty years. In both cases, Brannan’s nonchalance to the point of indifference is encapsulated in his vague descriptions of the transactions. In 1990, he received a letter from a gallery owner expressing a keen interest in exhibiting some Brannan paintings in his new establishment in Norwich: he was the same “chap who came last year and bought one of my 1950 type pictures.” Three years later, a private buyer and his wife from Nottingham visited the Welbourn studio, following up a favourable review of Brannan’s work in an old copy of “The Studio” magazine: “We, or they, unearthed a few ancient grubby looking 1950’s type things.”

A well-known painting from the 1950‘s which ended up in the reject pile for several decades, was a painting of Slaughterhouse Lane, Newark. The work was at the centre of a stormy controversy in 1959 when Newark Town Council refused to buy it, despite the strong recommendations of the Museum Committee and the distinguished artist Robert Kiddey. After this unfortunate incident, it was consigned by Brannan to the rejected paintings pile until 1989, in which year he generously gifted it to the town’s museum, along with a painting of Tallow Row from the same period. Both paintings are now part of the collection of the Sherwood and District Resource Centre in Newark.

The diaries make it clear that Peter Brannan spent a good deal of time trying to “rescue” paintings languishing in the reject pile, ones which had not been rescued in a different sense by buyers who obviously thought that their purchase required no further improvement.

An interesting example of Brannan rescuing a painting which had been exhibited years before provides a useful indicator of how the artist worked and, at the same time, creates complex issues relating to an accurate charting of the chronology of his work.

On the 18th September 1987, Brannan decided to repaint a large picture discovered in the reject pile “showing the carved head of a Bishop on a table”. For the next three weeks he made significant alterations to the original work by re-positioning the table, changing colours and putting new objects next to the large brown carved head. In passing, Brannan notes that he thought he had exhibited the painting in Lincoln in 1968. In this detail, he was absolutely right: the picture, now in a private collection, was shown at the 62nd Lincolnshire Artists’ Society Autumn Exhibition in 1968. Priced at 80 guineas, the painting was titled “Interior” (Exhibit 25) and was exhibited alongside “Seventeenth-Century Carved Head” (Exhibit 26) and “Street Scene” (Exhibit 117), both on sale for 35 guineas. Given the explicit reference to a carved head in Exhibit 26, but not in Exhibit 25, it would be logical to assume that the painting rescued from the reject pile was Exhibit 26, rather than Exhibit 25. However, based upon Brannan’s usual approach to pricing related to the size of a painting, the more expensive exhibit is almost certainly the rescued work of 1987. It is a big painting, measuring approximately 80 centimetres in length and 60 centimetres in width, which required Brannan to continually stand up when repainting it, much to his great discomfort.

In the course of the re-painting, Brannan typically experienced a series of conflicting emotions about the progress of the new picture. After the first session, he describes it as “big and bold and crude”. A few days later, after making decisive changes to the original, he reflects with some satisfaction on technical improvements made to “a very uneasy composition” and its “strange perspective”. The following day, more focussed upon what he might do with a snow scene and a beach scene found that day in the reject pile, he notes in passing that the painting is “better, but not very lovingly painted”. This sense of qualified success continues over the next couple of weeks, with the comments that it is “an improvement” and “going quite well”, but also that it remains “crude and obvious”. As Brannan reaches the end of the re-painting process, he provides the reader with information about the original 1968 work when he recalls it as being “rather too brown and gloomy”, and further, that the bishop’s head “hasn’t been re-painted too much”. His final comment on the 5th October 1987 is still doggedly ambivalent in its refusal to believe that the job has been successfully completed: “Possibly finished and better”.

In its present state, the painting is both unsigned and undated, and it seems that it was never shown in public until 2013, at the Newark Museum’s Spotlight Gallery Retrospective Exhibition, “Peter Brannan: the Newark Years”.

The re-painting of the 1968 work is an interesting episode in Peter Brannan’s artistic career which has clear implications for analysing his entire oeuvre. The first particular implication is that the painting exhibited at the Usher Gallery in 1968, and possibly at the Trafford Gallery, London, in the following year, as “Interior with Seventeenth-Century Carving” (Exhibit 24), now no longer exists. It has become a painting partially created in 1987, on top of a painting completed and exhibited in 1968. The second broader implication is that if there are other exhibited paintings which were taken from the reject pile and improved, albeit in a less radical way, then they too no longer exist, other than in an exhibition catalogue entry. Finally, and very obviously, the notion of establishing a definitive chronology of his work is thrown into some disarray.