ROSSETTI, Christina

Christina Rossetti

Drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The PRB, 1848

Sketch by Holman Hunt who has not included himself. One of them is James Collinson

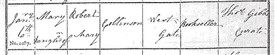

Record of Mary Collinson's 1818 baptism at St Peter's Mansfield

1825 record of James Collinson's baptism at St Peter's Mansfield

Note that his father's trade is given as 'Printer'

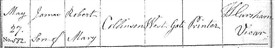

Burial of Robert Collinson at St Peter's, June 20th 1845

Penultimate entry on this page from the Parish Register

The Charity Boy's debut

He is leaving the spacious family hovel to go to the Ragged School

James Collinson's portrait of Christina

Christ Church, Albany St, Camden

Centre of High Church Tractarianism in the 1840s

Hardwick Old Hall

Where Christina was inspired on a picnic, August 1849

The Renunciation of St Elizabeth of Hungary

Brompton Oratory provided an unrealistic setting

'For Sale', Nottingham City Gallery

A copy in the Tate is called 'The Empty Purse'

Christina Rossetti in Notts: The Collinsons of Mansfield

By Ralph Lloyd-Jones

James Collinson (1825 – 1881) was one of the original seven members of the Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. Never as well-known or successful as those three, he remains a popular painter of Victorian genre subjects and was briefly engaged to Rossetti’s famous poet sister, Christina. Although not in the same league as Richard Bonington (1802 - 1828) of Nottingham, James Collinson is certainly an important artist, whose works now sell for hundreds of thousands of pounds, and who came from our county.

The Collinsons are recorded farming in the Mansfield area in the 18th Century, but the artist’s father Robert (1786 – 1845) had opened a bookshop in West Gate by the 1820s. His wife, Mary, came from Askham in Bassetlaw; they married in 1815 when he was 29 and she already 30. Their first child, also named Mary, was born at the end of 1817 and baptised at St Peter’s, Mansfield on January 6 the following year.

Their second child, Charles did not appear until 1823, James being born two years later on 9 May 1825 when his mother was 40 years old.

In the 1841 national census we find Robert aged 55 living above the shop in West Gate with Charles (18) and James (16), as well as one ‘F.S.’ (= Female Servant), Mary Eyre, also 16.

There is no sign of either of the Collinson Marys, nor have they been found living elsewhere in England in that census, so may have been travelling abroad at the time. That is certainly possible, since the shop, combined with Robert’s role as a sub-postmaster, brought in a good income and they were amongst the wealthiest tradespeople in mid-19th Century Mansfield. This is confirmed by the fact that they could, shortly afterwards, afford to send James to study at the Royal Academy in London. Millais and Holman Hunt were near contemporaries of his there; in fact he was a little older and had already exhibited The Charity Boy’s Debut at the RA Exhibition in 1847, making him the most established artist of the original PRB formed the following year.

Once the PRB had been set up, it was inevitable that James would meet Rossetti’s precocious (already published) 17-year old sister, though she had previously noticed ‘his heedful and devout bearing’ at Christ Church, Albany Street where they had both worshipped. At this time he was already a convert to Roman Catholicism, but appears to have attempted a return to High Anglicanism as a condition of becoming engaged to Christina. The originally Italian Rossettis were, of course, themselves converts to Protestantism; their father disliked the pope, Pius IX, and by extension the whole Catholic Church, for political reasons.

Robert Collinson had died aged only 59 in 1845, but Charles took over the family business, remaining with his wife and daughter at West Gate, while the widowed Mary and her unmarried daughter moved to a house in Pleasley Hill. In August 1849 Christina Rossetti came to stay for a while at both addresses, although her fiancé James was away, painting in the Isle of Wight, at the time. This visit had some impact on Christina’s work, especially a picnic trip to Hardwick, the Old Hall of which may have inspired a ruined castle in her fiction. She definitely discovered the unusual name Strawdy from a widowed framework knitter who lived nearby, as confirmed by the 1851 census.

Mrs Strawdy is a character in Christina’s short story Maude, and it has also been suggested that she took that title name from Charles and Anne Collinson’s baby daughter, though the same census shows that her full name was Mary Maud (- without the 'e'. Tennyson’s famous poem which greatly popularised that name was not published until 1855).

Christina wrote of James Collinson’s mother (aged 64) that ‘she retains a dignified beauty which inspires respect and love; her conversation is full of spirit and goodness. She very much resembles her son, of whom she speaks with tender affection.’ (Marsh, p.101) She also mentioned that James’ sister, then aged 32, had an ‘eruption’ – perhaps a birthmark? – on her face. As well as visiting local sites like Hardwick, they played chess and bagatelle and, sounding rather like Jane Austen, Christina wrote to her brother William ‘In my desperation I knit lace with a perseverance completely foreign to my nature.’ - !

She seems to have been relieved to spend her last Mansfield week in West Gate at Charles’ bookshop, one biographer suggesting that this was because ‘Anne Collinson and her sister Carrie were closer than Mary to her own age’ (Marsh, 102-3).

It is difficult to agree with another writer who says that Christina’s ‘letters from [Mansfield] only reveal her awkwardness and longing for home’ (Duguid), since she appears to have enjoyed the visit, lace-making notwithstanding. It was definitely James' religious crisis that led them to break off the engagement, rather than any ‘awkwardness’ that she may have felt towards his family. In 1850 he completed his most overtly Pre Raphaelite work, The Renunciation of St Elizabeth of Hungary.

This painting shows the still young queen refusing to remarry after the death of her devout husband, vowing instead to enter a convent. It is clear that the Catholic Collinson was empathising with that pious royal lady when he chose such an obscure subject, not well-known beyond Hungary. If there was any ‘awkwardness’ it was very much on his part and may easily be detected in this piece of art. Not only did he end the engagement, but Collinson cited his Catholicism as a reason for leaving the artistic Brotherhood. He even sold all his paint and brushes and tried to train for the priesthood; but changed his mind and married a Catholic woman, Eliza Wheeler in 1858. In his later career he usually stuck to safe, secular genre paintings, avoiding anything controversial. A typical example is For Sale (1857) which can be seen in the Castle Gallery at Nottingham.

There is an unsubtle double entendre here, and such moralising works are the opposite of everything the PRB stood for. James Collinson died in 1881. Christina Rossetti, who died unmarried in 1894.

(Charles and Anne Collinson had given up bookselling in Mansfield by 1861, moving to Eastwood. He went back to his grandfather’s work of farming, having 240 acres and employing six men and two boys according to the census of that year.)

Bibliography

Marsh, Jan : Christina Rossetti, a literary biography; Jonathan Cape 1994

Duguid, Lindsay: Christina Rossetti in The New Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)