The Realisms of Peter Brannan

Snow Scene 1961

Private Collection, courtesy of the Artist's Estate

Back Lane 1962

Private Collection, courtesy of Artist's Estate

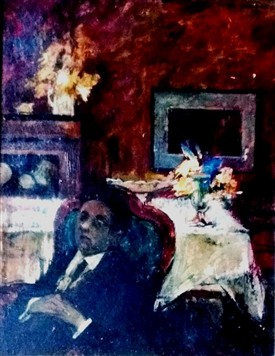

Dark Interior c.1955

Private Collection, courtesy of the Artist's Estate

East Coast Beach 1973

Private Collection, courtesy of the Artist's Estate

Reading in Bed 1955

© Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections, courtesy of Artist's Estate

By Dr Malcolm Moyes

In October 1958, H M Sutton, Principal of Mansfield School of Art, was invited by the Lincolnshire Artists’ Society (LAS) to critique their 52nd Annual Exhibition, held at the Usher Gallery in Lincoln. At the time, the reputation of the Society as a representative of high standards of artistic creation was well-established, having been enthusiastically praised and endorsed throughout the decade by such influential critics as Eric Newton, Robert Melville and Sir Albert Richardson.

It therefore must have come as a shock to the members of the LAS to be told by Sutton that he had found the exhibited works inadequate in terms of creativity and imaginative invention. It must have come as a relief to Peter Brannan, however, that his four works on show, On the Beach (Exhibit 19), The Mount, Newark (Exhibit 25), Snow Scene, Newark (Exhibit 27) and Portrait (Exhibit 37), not only escaped the critical carnage, but were singled out for exceptional praise. Sutton remarked on Brannan’s accomplished technical handling of paint and described him as an artist who was a realist, with a fine streak of individual vision.

Sutton’s description of Brannan as a realist is a useful point of departure for considering some aspects of his work: whilst we cannot be entirely certain what Sutton was commenting upon, as only one of the paintings is without doubt in the public domain, the evidence of other paintings completed and exhibited in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s by Brannan may provide a useful guide in considering exactly what Sutton meant.

By common consent, the terms “realist” and “realism” are not always easy to pin down and are sometimes so flexible in their usage that they became almost meaningless. However, the specific historical and cultural contexts of Sutton’s comments are helpful in understanding what he had in mind when he labelled Brannan a realist.

By 1958, the concept of realism in painting was embedded in the discourse of contemporary British Art, as it was in discussion of contemporary British Literature. From the early 1950’s in London, there had been exhibitions of Realist and New Realist British Art, promoted in particular by the critic John Berger, as part of a Marxist agenda for social and political reform. Broadly speaking, realist painting focussed upon the ordinariness of everyday life, warts and all, and in part was an attempt to make art more immediately accessible and relevant to ordinary people. In keeping with the sombre mood of post-War austerity there was a stark focus upon common experience lived by the many – a sometimes uncompromisingly raw vision whose bleakness some artists intensified by way of a limited drab colour range.

The painting by Peter Brannan titled Snow Scene, Newark is almost certainly the one which was at the centre of controversy in early 1959 when it was rejected for purchase by the Newark Town Council, despite recommendations by its Museum Committee, and supported by the internationally renowned local artist Robert Kiddey. The offence and outrage caused was a response to the subject matter of the painting whose focus was Slaughterhouse Lane, one of the more shabby areas of the town, depicted by Brannan as a grim scene of urban decay and dangerous dereliction. The work is essentially a gritty snapshot of a drab world rinsed of all beauty, charm and delicacy, in sharp contrast, for example, to the pretty, more palatable C19th Romantic paintings of Newark by Peter DeWint. There is a strong sense that the rejection of the work was as much rooted in a disapproval of a contemporary trend in painting as it was in a wounded civic pride. Ironically, but not surprisingly, the rejected painting was accepted for hanging later that year at the 112th English Art Club Exhibition, staged at the prestigious RBA Galleries in Suffolk Street, London.

The unflinching and unvarnished urban realism of Snow Scene, Newark, made even less enticing by a foreground of dirtied snow, is also seen in other Brannan paintings of this period. Snow Scene, completed in 1961, with its dismal mish-mash of buildings, telegraph wires, spiky leafless trees and discoloured snow, is no less unremitting in its drabness, despite the inclusion of two small figures; indeed, it might be argued that their inclusion – random, fleeting and seemingly without significance - does more to intensify the austerity of the scene than to alleviate it.

The cheerless realism of Back Lane, completed in 1962, hinted at in its uninviting title, is created by way of a dour scene of featureless people, parked cars and dowdy buildings packed tight against each other; these in turn are juxtaposed against an abandoned house with half its roof missing, situated on the other side of the lane. The uncomfortable ugliness of the scene is completed by the mangled, discarded broken bike, seen lying amongst a pile of indistinct rubbish which is spilling on to the kerbside.

Brannan’s rendition of contemporary urban life, with no attempt to hide its blots and imperfections, represents one aspect of realism in British Art current in the 1950’s and early 1960’s. Another aspect, closely related, but without the pejorative and potentially challenging political connotations of neglect and degeneration, is in his choice of mundane subjects, familiar and devoid of any conventional aesthetic appeal. It is realism seemingly intent on giving significance to the ordinary and the easily overlooked, a deliberate choosing of incidents and situations from everyday life.

A review of the twenty-seven titles on show in Peter Brannan’s First One-Man Exhibition at the Trafford Gallery in London’s Mayfair in 1960, strongly suggest this realism of the commonplace. It is a thematic focus which positions Brannan in the tradition of Realist Art, from Walter Sickert and the Camden Group, the Euston Road School, through to the so-called Kitchen Sink artists John Bratby, Derrick Greaves, Edward Middleditch and Jack Smith, intent on creating art from the prosaic and the ordinary. It may be significant in this connection that a year earlier Brannan had exhibited a work intriguingly titled Kitchen Interior (Exhibit 14) in the 53rd LAS Exhibition.

In the First Trafford Exhibition, there is still a focus on the everyday townscape of Newark, evident in such titles as Newark School (Exhibit 3), Street Scene, Newark (Exhibit 8), Newark Bridge (Exhibit 10) and Mount Lane, Newark (Exhibit 13) – possibly the same work in the 1958 LAS Exhibition. It is the realism of the everyday in the sense of it being part of the shared experience of local people and Peter Brannan himself, living and working in the town as a school teacher. At the same time, there is also an interest in the ordinary life of public interiors, suggested by Bar with an Old Lady (Exhibit 12) and The Barman (Exhibit 22), as well as the more quiet and intimate domestic moments of private interiors, indicated by such titles as Reading in Bed (Exhibit 16), Woman Doing her Hair (Exhibit 19) and Dark Interior (Exhibit 20).

Brannan’s taste for the everyday, almost to the point of ironic banality, is evident in his choice of public car parks as a subject. Newark Car Park and the more specific Lombard Street Car Park, for example,were both exhibited at Trafford Gallery One-Man Shows, in 1962 and in 1969 respectively.

A clear sense of urban realism is also evident during this period, and indeed beyond, in Brannan’s frequent referencing of popular culture, in particular the impact of the bingo craze on existing venues of popular entertainment, such as the Dance Hall, Theatre and Cinema in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s.

Dancing at the Dome, completed in 1963 and currently on loan to the Newark Town Museum, is a representation of the faded glitz and glamour of the Old Time Dance Hall, with its contrived Moorish dome and towers flanked by adverts for bingo. A slightly later version titled Newark Dance Hall, completed in 1969, captures the ubiquitous presence of the popular urban pastime more pointedly, by imaginatively turning the venerable mid-C19th Newark Corn Exchange building into a Dance Hall which is in the process of being superseded by the seductive promise of “great bingo prizes”.

View of a Town, completed in 1968 and purchased by the Newark Town Museum soon after, is a panoramic aerial view, typically incorporating elements from a variety of urban locations known to Brannan. The painting references contemporary local businesses through various signs and adverts, but the dominant image in the right foreground is of the imposing Tower Cinema, possibly defunct, and like the Newark Dance Hall, being turned into a Bingo Hall for the enhancement of popular urban night life.

In a sense, Peter Brannan never stopped being a realist in terms of his artistic vision. This is particularly true of his obsessive and distinctive representations of the working class at play in the holiday resort of his home town of Cleethorpes and of the East Coast in general, one of which, On the Beach, Sutton probably viewed in the 1958 LAS Exhibition. As with the realism of some of his Newark-based work, Brannan’s coastal paintings capture everyday life being lived in familiar here and now contexts; although unlike some of that work, and despite the sometimes sombre palette, there is little sense of the bleak and depressing. The mass tourism of the East Coast seaside holiday may have seen more prosperous days, but there is no sense of desperately and nostalgically holding on to a faded past or representing a maligned English bucket and spade holiday with a satiric glibness.

His many seaside scenes, created over time in a variety of styles, depict ordinary families on holiday, doing unexceptional things. These souvenirs of a careless day or week’s escape from work, at a far remove from the sentimental and picturesque summer idylls of many beach paintings, focus upon the commonplace realism of holiday relaxation and popular entertainment: the cart and donkey rides; the hired deckchair on the beach; ice-cream stalls touting for trade; the exhilaration of the roller-coaster and big-dipper; and the latest pier attractions of bingo and dancing.

In some paintings there is a sense of dogged and determined fun despite the fresh winds coming off the North Sea and the glowering sky hanging over the beach like a threat; but the scenes remain vibrant, often charming, as ordinary people go about their unremarkable business of enjoying themselves in traditional holiday locations.

Peter Brannan, it seems, was a provincial realist whose work met with critical acclaim and commercial success in London in the late 1950’s and 1960’s. However, shifts in artistic taste away from realism towards less figurative, more enigmatic modes of art, meant that his paintings would, like those of the Kitchen Sink Artists, have an increasingly less fashionable metropolitan appeal. Apart from the occasional work exhibited at the RBA Galleries during the 1970’s and 1980’s, Brannan’s last significant outing in London was in 1971, his Sixth One-Man Exhibition at the Trafford Gallery. A number of the thirty-one paintings on show, such as Gravel Pit (Exhibit 2), By the Canal (Exhibit 20) and Factory Scene (Exhibit 24) seem to represent the grittier aspects of realism, whilst such titles as Seaside Illuminations (Exhibit 3), Cleethorpes Beach (Exhibit 6) and Café on the Dunes (Exhibit 21), belong to that larger group of paintings whose realism is less disconcertingly humdrum and challenging in its subject matter.

Peter Brannan’s paintings, and especially his coastal scenes, continued to sell at exhibitions in his native Lincolnshire and beyond, until his death in 1994. Clearly, the more gentle realism of the holiday resort, less confrontational and brutal than such works as the Snow Scene, Newark and Back Lane, had a more sustained appeal to the public, who were very pleased to buy them and hang them in their living rooms.

Malcolm Moyes