The True History of Robin Hood

Earliest image of Robin from the Gest of Robyn Hode

Caxton saved money by also using this picture for Chaucer's Yeoman. Horses did have smaller heads in those days, but nobody could fire a longbow from the saddle

King John hunting

This is the correct royal image - he does not want it spoilt by outlaws poaching his deer

William Langland

Dreaming about Robin Hood?

The Sheriff of Nottingham

Alan Rickman in 'Robin Prince of Thieves' (1991)

The death of Robin Hood

From 'The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood' by Howard Pyle (1883)

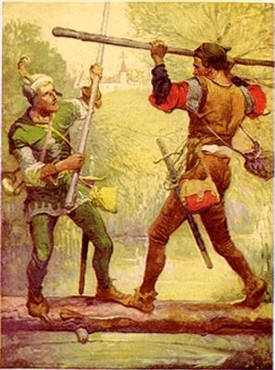

Robin meets Little John for the first time

A classic myth, as illustrated by Pyle

Sir Guy of Gisbourne

Basil Rathbone in 'The Adventures of Robin Hood' (1938)

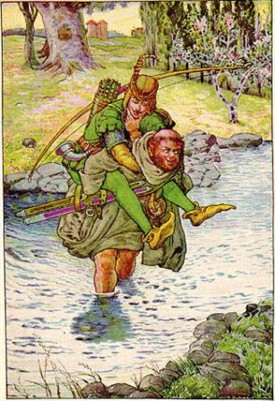

Friar Tuck carrying Robin

Another of the American artist Pyle's 1883 illustrations

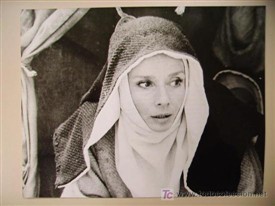

Maid Marian

Audrey Hepburn in 'Robin and Marian' (1976)

16th Century image of Robin with his weapons

19th Century stage Robin

William Payne (1803-1878) in a pantomime

Robin Hood statue, Nottingham

By local sculptor James Woodford (1952)

By Ralph Lloyd-Jones

The story of Robin Hood and his outlaw followers is a legend that makes Nottinghamshire famous all over the world. Although other parts of England, including the nearby Barnsdale area of West Yorkshire (once also Royal Forest), have some claims to be associated with him, the basic story always centres on Nottingham and Sherwood Forest.

There is much debate about exactly when ‘the real Robin Hood’ lived, though ideally the tale must be set in the early 1190s when Richard I was King of England, but absent on Crusade. In reality Richard had left a regency which Prince John ignored, setting up an alternative ‘court’. When Richard finally returned in 1194 he had to fight his brother, even unsuccessfully assaulting Nottingham Castle which was held by John’s followers. Thus the legendary Robin and his men are portrayed as outlaws only to John’s illegal regime; ‘Good King Richard’ returns and pardons our heroes, punishing any surviving baddies at the same time.

The first written mention of Robin Hood occurs in William Langland’s Piers Plowman (1377). It is clear that he was already a well-established folk hero who needed no further explanation. Indeed, there are legal records of real Medieval fugitives all over the country being given the nickname ‘Robehod’, or variants like ‘Hobbehod’ from as early as the 1260s.

The mid-15th Century Gest of Robyn Hode was one of the earliest books printed in England by Caxton. Much of this is set in West Yorkshire (including the death and burial of Robin at Kirklees Priory), but it also has an archery competition in Nottingham and the evil Sheriff as one of Robin’s enemies. There were several unpopular ones in reality, including Eustace de Lowdham (13th Century) and another called John Oxenford a hundred years later. Since, as mentioned above, Nottingham Castle had been held for Prince John in 1194, he clearly had his supporters in our county.

The other established characters appear one by one in various written versions, though they must have been famous long before anyone put pen to parchment. Little John provides brute quarterstaff brawn to Robin’s subtle longbow brain. The various tales of a friendly ‘fight’ with a stranger, often followed by a trick ducking in the river, occur in stories from many cultures e.g. Sinbad and the Old Man of The Sea in the Arabian Nights and the legend of St Christopher.

As well as Little John, there were always monks in the stories, but a real outlaw priest, Robert Stafford, operating as a murderous criminal in Sussex and Surrey 1417-1429 called himself Friar Tuck – which may have helped him to survive 12 years on the run. Sometimes it is the Friar who drops Robin in the water, as well as Little John knocking him off a rickety bridge in other versions of the same theme.

Other instantly-recognisable characters who have been added down the centuries are Allan A Dale the minstrel (dating only from the 1600s) and Will Scarlet, still shown in film and TV versions dressed in red, though his name is a corruption of Scarlock, or Scathelock – a much better name for an outlaw. Then there is Much (Midge, or Mitch) the Miller’s son, no relation to the famous ‘Miller of Mansfield’ who features in his own, separate, old story.

Sir Guy of Gisbourne is a bounty hunter in the Gest who only just loses an archery competition to Robin who then kills him with his Irish knife and sticks his head on top of his bow. The very specific ‘Irish knife’ must have been instantly recognisable to a Medieval audience, perhaps similar to mentioning something like a Bowie knife today. Robin wears his dead enemy’s clothes and even blows his horn to trick the Sheriff and his men into thinking Guy beat him. Gisbourne tends to survive longer in modern films, providing a useful sidekick to the Sheriff and his otherwise anonymous soldiers.

Maid Marian is traced back to a French play Le Jeu de Robin et Marion by Adam de la Halle (c.1283). Although Robin Hood is well-known as Robin des Bois (Robin of the Woods) in France, the ‘Robin’ in Le Jeu is not necessarily our Hood, but simply portrayed as ‘a knight’, while ‘Marion’ was originally a shepherdess. By the early 16th Century Marian and Robin Hood were accepted as the May Queen and King throughout England, her place assured in the legend. Nowadays she is always a feisty noblewoman who has to avoid the unwanted advances of the Sheriff (and sometimes Guy too), providing love-interest for our Robin - who generally has to rescue her from the Castle; though she can manage quite well by herself, for example often being handy with a bow of some sort.

Real longbows were massive specialist weapons which required great strength and constant practice from childhood, the reason they were so quickly replaced by guns once firearms were developed. In the hands of an expert longbows can kill at distances of up to nearly 300 metres. At closer range they could be fired with extreme accuracy and easily pierce armour. The bows and arrows seen in movies are a pale imitation of the true Medieval ones.

The Forest, too, was very different from what we (and Hollywood) always imagine. It would have been more like an open ‘Chase’ with plenty of room to gallop between widely-spaced trees. Those trees were predominantly oaks which need a large area to themselves in order to mature properly. Thousands of people were employed throughout the ‘Shire Wood’, mainly in forestry, raising deer and in the actual hunting, one of the attributes of Medieval kingship. At Clipstone there was a huge, mostly wooden, palace, dating back to Anglo-Saxon times. Most Medieval kings and their queens spent time there; it was only abandoned when Henry VII (ruled 1485-1509) effectively established Westminster as the court powerbase and fixed national capital for holding parliaments.

Sir Walter Scott includes Robin as a character in his most popular novel, Ivanhoe (1819), which has also proved attractive to Hollywood and television. Scott makes him a 'Saxon' fighting 'Normans', historically quite impossible over a century after the Battle of Hastings. It also seems to be the origin of Hood turning out to really be the noble ‘Robin of Locksley’, which has become yet another part of the accepted ‘correct version’ of the story.

The basic plot, that a gang of jolly thieves – Merry Men – are hiding in the Forest, fighting an unjust and greedy ruling class, robbing from them - the rich - and giving to the poor has a universal appeal. The fact that Robin is a cunning outlaw, not entirely goody-goody, greatly adds to his attractivness. He is the original mysterious robber in a hood, watching over all victims of oppression everywhere, Nottinghamshire’s Robin Hood.